by Brad Houle, CFA

Principal

Head of Fixed Income

Portfolio Management

As we look ahead to the Federal Reserve’s December 10 policy meeting, markets are pricing in a greater than 90% chance of a .25% cut in the Fed Funds rate. As my colleague Blaine Dickason wrote last week, the Fed is laser-focused on the jobs market. While this week’s labor market data points to a cooling trend, it doesn’t suggest a contraction. Challenger, Gray & Christmas’s November jobs report shows sharply reduced layoff announcements compared with the prior month, while initial and continuing jobless claims remain at levels consistent with a healthy hiring environment. Together, these indicators show a labor market that is easing but still fundamentally resilient, providing clearer evidence of moderation rather than meaningful deterioration.

Understanding which interest rates the Fed controls directly versus what the broader bond market determines is essential for setting expectations. The Fed sets short-term interest rates, most notably the federal funds rate. That policy rate influences money market yields, short-term Treasury bills and borrowing rates tied to overnight or very short-duration financing. When the Fed cuts rates, yields on money market funds typically decline as portfolios reinvest maturing securities at lower prevailing yields.

Long-term rates, however, tell a different story. The Fed does not “set” the 10-Year Treasury yield or the 30-year mortgage rate. Instead, the market determines those yields based on expectations for future inflation, economic growth and the supply of Treasury debt. At times, long-term rates fall alongside Fed cuts because investors anticipate weaker economic conditions ahead. Other times, long-term yields can rise even as the Fed eases, particularly when inflation expectations or growth forecasts remain elevated.

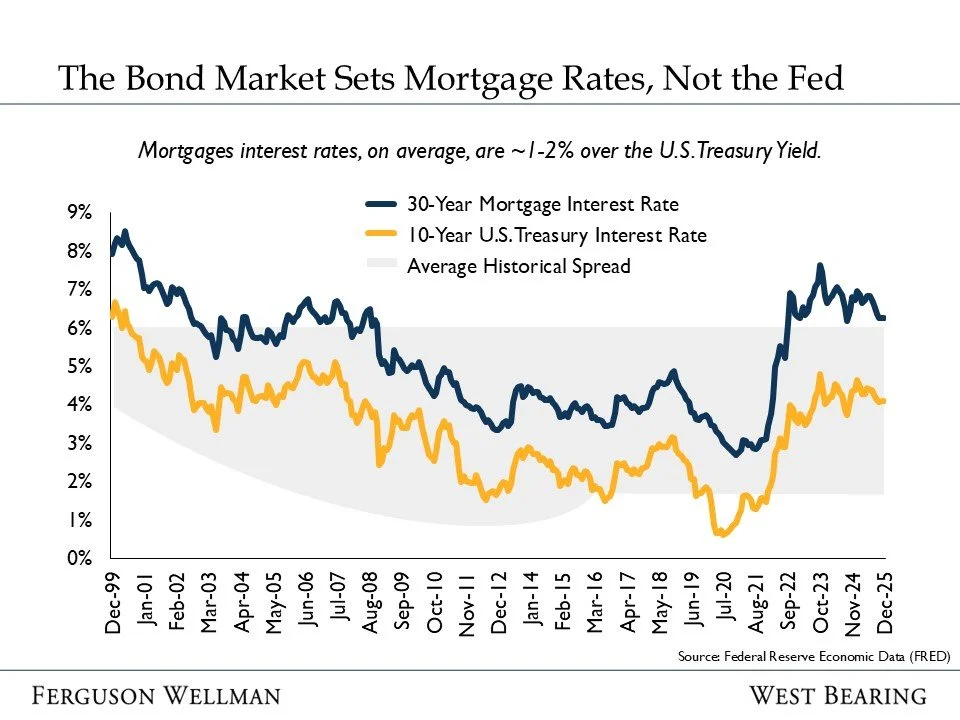

A tangible example is the U.S. home mortgage market. A typical fixed mortgage interest rate closely tracks the 10-year Treasury yield, not the Fed Funds rate. When long-term treasury yields surged from 2022 through 2023, mortgage rates climbed from below 3% to above 8%. Likewise, when long-term yields eventually decline, mortgage rates tend to follow, making housing affordability tied more to market expectations than to Fed policy alone. As a rule of thumb, mortgage interest rates are 1.5% to 2.5% above the 10-year Treasury rate, also known as the spread. The greater the economic uncertainty, the higher the mortgage interest rate for borrowers relative to the 10-Year Treasury.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

This distinction between short- and long-term interest rates is central to how monetary policy reaches the real economy. While a Fed rate cut may lower floating-rate funding costs for corporations and reduce money market yields, long-term borrowing costs—from mortgages to municipal financing—will continue to trade on market expectations.

Takeaways for the Week

The Federal Reserve controls short-term interest rates and the bond market controls long-term interest rates, which in turn affect interest rates on home mortgages

We expect the Federal Reserve to lower short-term interest rates on December 10 by .25%

Labor market data from this week show that it is easing but still fundamentally resilient